As transit agencies commit to prioritizing the needs of low-income individuals of color, new methods to achieve mobility equity are being developed.

By Stephanie Jordan

Managing Editor

Transit California

One outcome of the coronavirus pandemic is the spotlight it has put on public transit dependent riders. As ridership plummeted throughout California when COVID-19 restrictions advanced, those still boarding public transit were revealed to be lower-income essential workers, people with disabilities, students, and people of color. In response, many transit agencies have a renewed commitment to the most vulnerable members of their communities. Service delivery, altered due to ridership changes, operator availability, and budget during COVID-19, is being studied by transit operators with an eye toward the future, questioning in a post-pandemic world, what should our transit system look like? And how do we ensure that our planning, policy, and decision-making structures will equitably deliver mobility benefits to our low-income communities of color?

This is not an entirely new conversation for public transit agencies. Agencies have had equality programs as a result of following Title VI requirements for some time, and some agencies, like San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA), have a history of moving beyond Title VI requirements because Title VI stops short of a deep commitment to racial justice.

“The way to view it is this,” says Therese W. McMillan, Executive Director of the San Francisco Bay Area's Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the Executive Director of the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), and former Deputy Administrator and Acting Administrator for the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) for six and a half years, “It is always important to have some level of baseline and in a regulatory format that is a requirement. One of the really significant accomplishments I helped lead at FTA was a revamping of our Civil Rights Program and bringing Title VI up to a much more significant and consistent set of directives. What regulation does - and this is an important context to remember - is Title VI is a regulatory reflection of the Civil Rights Act and in those cases it is incredibly important to have a baseline that everyone adheres to but that’s the necessary floor – it’s not the ceiling.”

McMillan goes on to say, “What we are beginning to understand and advance in our work in this area of equity, is to make sure there is an understanding between equality and equity. The distinctions are important – equality is that foundation where you start, but it is not enough in terms of achieving the objectives that we are moving towards. When we talk about Title VI that is the foundation of equal treatment. If you look at our history that has not always been the case. Just getting to that point is huge. There are some parts of this country where we still need to establish equality. But to achieve the equity outcomes that we are wanting – of creating opportunity for everyone, especially for people of color – that takes a deeper commitment to racial justice.”

Greenlining Institute’s Leslie Aguayo, an urban planner and advocate with experience in poverty alleviation, asset building, affordable housing, equitable transportation and community outreach strategies, is seeing a favorable shift toward equity.

“For years Greenlining and our partners across the country have been working hard to ensure that the private sector and public sector see equity as an opportunity and it is working,” she says. “There are 157 jurisdictions across the country that have implemented racial equity action plans within their policies, programs, and regulations. Times are changing and cities are raising the bar on equity. We have new standards for how mobility services must benefit communities and as a result many mobility companies are following suit by implementing equity programs into their services. Now that our organization spends less time convincing people that equity matters, our team has been focusing on developing an actionable roadmap for how to achieve equity.”

Operationalizing Equity

In its Making Equity Real in Mobility Pilots, Greenlining offers resources and tools, including four steps to making equity real, noting, “These resources and tools are intended to guide government agencies, companies, and other entities in the planning, development, implementation, and evaluation of equitable mobility projects. In other words, this packet will guide you on how to operationalize equity.” The nine page document is packed full of recommendations for approaching equitable mobility pilot projects, including equity analysis, examples of community engagement and decision-making, and over 20 questions where responses can build a baseline for operationalizing equity.

“The actionable roadmap for how to achieve equity uses four pillars,” explains Aguayo of the steps. “These include making sure equity is embedded in missions, visions, and values, there is an equitable process, there is an equitable implementation of those outcomes, and there is equitable measurement and analysis to make sure that the outcomes actually measure what you intended to achieve in the first place.”

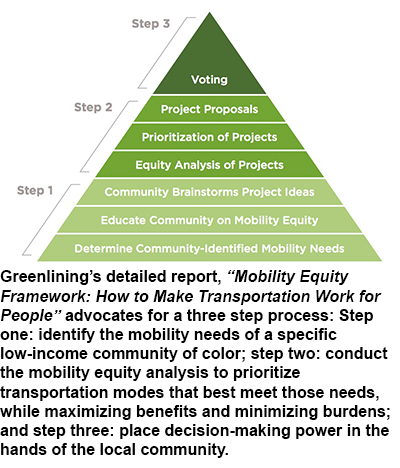

One of the resources within the Making Equity Real in Mobility Pilots is a link to Greenlining’s detailed report, “Mobility Equity Framework: How to Make Transportation Work for People." Authors Hana Creger, Environmental Equity Coordinator, Joel Espino, Environmental Equity Legal Counsel, and Alvaro S. Sanchez, Environmental Equity Director write: “Too often, transportation decisions do not meaningfully address these racial inequities, and may reinforce racially segregated geographies and spatial inequality, which stem from a long history of discriminatory policies like redlining, racial covenants, and housing policies that specifically excluded communities of color from economic opportunities. These inequities persist when policymakers fail to understand the mobility needs of low-income people of color, fail to include them at the decision-making table, fail to determine who benefits or suffers from transportation decisions, and fail to track and measure success from an equity perspective. To remedy this, our proposed solution prioritizes equity and community decision-making power in transportation planning and investments.”

The report advocates that to achieve mobility equity in transportation planning and investments, planners must prioritize social equity, defined as the fair and just distribution of societal benefits and burdens, and community power that allows marginalized communities to influence decisions in a way that addresses their needs and concerns.

At its core, the Mobility Equity Framework gives communities and advocates a tool to analyze, evaluate, and compare different transportation modes based on their ability to enhance mobility, improve health, and increase economic opportunities for low-income communities of color.

Four Forms of Equity

Through the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, Mary Buchanan, a Senior Research Associate at TransitCenter and Natalee Rivera, a TransitCenter Graduate Program Fellow, published What Transit Agencies Get Wrong About Equity, and How to Get It Right that focuses on the intersection of race, equity and public transit in America, specifically commenting on what agencies are missing about equity.

The authors write, “All transit agencies must grapple with committing the resources necessary to effectively identify inequity and remedy it. But in 2020, the mandate to ensure an equitable transportation system is more urgent than ever. Centering equity cannot be optional for transportation planning and investment to appropriately serve the riding public and improve the mobility outcomes of local riders, workers and communities.”

The paper is framed around four forms of equity. The authors state, “Equity acknowledges that racism, classism and other injustices have created barriers that make it hard for some people to access a system, and it corrects by committing extra resources to marginalized groups so they can fully participate.”

The Urban Sustainability Directors Network identities four forms of equity, which Buchanan and Rivera apply to transit in this way:

Distributional equity asks if effective and safe transit is available to all, and if its burdens, such as air pollution, are equally shared. Extensive analysis on how transit serves people measures distributional equity.

Procedural equity ensures that everyone who would ride transit can contribute opinions, ideas, and information that affect decisions about how transit operates. Robust public engagement creates space for procedural equity.

Structural equity relates to who holds decision-making power over operations. Transit workforces and governing bodies must reflect the diversity of the communities they serve, empower all workers to decision-making and legitimize their contributions.

Restorative equity can be understood as justice. It acknowledges systemic harms, past and ongoing, against certain people and ensures commensurate investments to repair those harms. The push to fund public transit, equal to its worth to communities, combats policies that chronically devalue transit because policymakers disregard it as a core service for low-income people of color.

Of the four forms of equity, the authors advocate that the ultimate goal is restorative equity, but are quick to point out that partially addressing equity will result in a failed attempt at intended outcomes. “Transit agencies must begin with a multidimensional approach to equity,” state the authors.

SFMTA Equity Toolkit

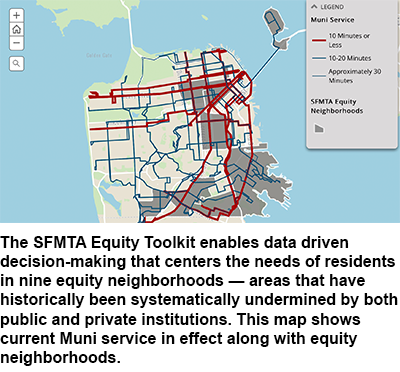

San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) began developing its Muni Service Equity Strategy in 2016 with the goal to identify and address high priority transit needs in neighborhoods that rely on transit service the most with tangible solutions that can be implemented quickly (within one to two years) and deliver measurable improvements. The Muni Service Equity Strategy focuses on improving transit performance in San Francisco households with low incomes, private vehicle ownership, and race and ethnicity demographics. As part of the analysis, SFMTA staff reviewed Clipper data to identify routes heavily used by seniors and people with disabilities.

When the coronavirus struck, economic and public health data showed that most San Francisco essential workers live in historically underserved equity strategy neighborhoods. If they are dependent on public transportation and cannot get to work reliably, not only does the city suffer, those workers could lose their jobs. This is why improving job access for essential workers is so important to SFMTA and why the agency developed its SFMTA Equity Toolkit that helps improve Muni service for San Francisco’s most transit-dependent residents.

SFMTA Public Relations Officer Mariana Maguire stated in a blog post, “The SFMTA Equity Toolkit helps us improve Muni service for San Francisco’s most transit-dependent residents and essential workers. Using data layered with mapping we are able to improve access to jobs and key destinations by identifying and fixing gaps in service.”

The agency says the toolkit focuses on San Francisco’s nine neighborhoods identified by the Muni Service Equity Strategy and is part of SFMTA’s Transportation Recovery Plan for rebuilding its transportation system to be more just and equitable for the city’s historically marginalized communities. Today people living in neighborhoods identified by the Muni Service Equity Strategy have more Muni service than people in other neighborhoods, who generally have more alternatives to public transit.

“For example, in the Bayview, where there is a high concentration of essential workers, the existing Core Service Plan has made essential jobs within a 30-minute commute 12 percent more accessible than before the COVID-19 pandemic,” explains Maguire. “Jobs within a 45-minute commute are 55 percent more accessible. The Equity Toolkit shows that we still have work to do to ensure adequate Muni service for those who need it most right now. We will continue to use what we learn to improve our Core Service Plan and increase access to essential jobs and services for San Francisco’s most vulnerable communities.”

Expert Advice

As public transit agencies pursue equity programs, more tools and resources will become best practices. While a panelist on Recognizing and Addressing Racial Bias in Your Practices and Programs at the California Transit Association’s virtual 55th Annual Fall Conference & Expo in November, KeAndra Cylear Dodds, Executive Officer of Equity and Race at Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA Metro), said her agency is in the development phase of a Budget Equity Tool.

“Part of equity is making sure that there is equity in the distribution of resources,” she says. “We must be sure to meet the needs of those that are most in need, from a high level perspective looking at everything from where we invest, our services, our programs, who utilizes them, and the benefits or burdens they provide. Part of the research has shown us one equity approach is looking at budget adjustments. How can you maximize equitable outcomes? With a Budget Equity Tool – when looking at specific communities, people of color, with disabilities, low income – we will be able to better understand the potential impacts of a budget decision.”

Cylear Dodds also noted that as equity tools are developed, it is important to remember that tools are only as helpful as the people that know how to use them and stressed the need for training.

Cylear Dodds’ fellow conference panelist, Dante King, an Anti-Racism Specialist and Leader of Cultural Change, Equity, Employee Experience, and Engagement, had this advice for executive-level managers pursuing equity: “When it comes to issues around race, leaders need to use their authority and power in a way that will lead to adequate and acceptable changes. If you are someone that has never belonged to a group that has been oppressed by people that have racial biases and use power to oppress you, then you have not lived with the psychological, sociological, mental, emotional, spiritual, economic, and physical harms and realities of it. As much empathy that you think you have – while it is coming from a place of authenticity and sincerity – it is not a lived experience. So if someone like me from your agency brings solutions to you as a non-Black or Brown person, you need to listen, you need to act, and you need to trust. To not trust and to not implement equity recommendations shows you really aren’t in solidarity. You may not be as concerned about equity issues as you think you are. As an ally and a leader, use your power to make decisions based on the insights given to you.”

Even as the crisis facing all public transit systems because of the pandemic continues, there is a unique opportunity to shape the future of mobility by infusing equity into recovery strategies to enhance mobility, improve health, and increase economic opportunities for low-income communities of color.

"Some may say the pursuit of equity slows us down in reaching the clean transportation future that we desperately need,” says Aguayo. “But it doesn’t. In fact we won’t reach our climate goals unless equity is baked in at the very beginning, allowing everyone access to a clean transportation future. If we fail to put equity at the center of this new mobility revolution it will only create problems that we will have to face. We must act boldly or we risk cementing inequity in our society for the next 100 years, if we don’t do this right.”